Scientists observed meteorological changes caused by the shadow of the moon during a total solar eclipse in 1900

On the morning of May 28, 1900, thousands of people across the southeastern United States gathered to witness a rare and spectacular sight as the moon cast its shadow across the sun and darkened the skies. The total solar eclipse carved a path from New Orleans, Louisiana, to Norfolk, Virginia, spanning over 925 miles and obscuring the sun for around 1 to 2 minutes in many locations.

Among the skywatchers were teams of scientists and volunteers who stood ready to document a variety of atmospheric conditions with the hope of advancing meteorological science. And, for one of the first times in history, these teams corroborated how an eclipse affects Earth’s atmosphere.

In fact, scientific expeditions set out with the missions of examining everything from the solar corona to the eclipse’s shadow bands. Their destinations fell within the path of totality—the narrow area of the total eclipse where the moon completely blocks the sun. And, one such expedition, led by the U.S. Weather Bureau, traveled to Newberry, South Carolina, to conduct an in-depth meteorological study of the event.

Why Newberry, South Carolina?

Before setting out for Newberry, Weather Bureau scientists surveyed historical meteorological conditions across the Southeast as they searched for the perfect location to conduct their observations during the eclipse. And, their examination of cloudiness observations in 1897, 1898, and 1899 found that the least cloudy conditions were likely to occur in Georgia and South Carolina on May 28,1900.

Additionally, as the eclipse tracked eastward, the duration of totality increased from about 72 seconds near New Orleans to about 100 seconds near Norfolk. This information, combined with the cloudiness data and a desire to select a location higher in elevation, led the Weather Bureau scientists to choose Newberry as their vantage point.

What Were the Weather Conditions Like on May 28, 1900?

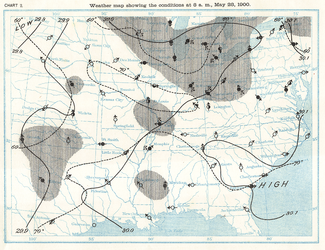

Fortunately for the Weather Bureau scientists, their bet on Newberry paid off. In fact, the weather conditions were ideal for viewing the eclipse along much of its track.

As described in Eclipse Meteorology and Allied Problems, a 1902 U.S. Weather Bureau Report,

“There was a little cloudiness and a showery condition in Georgia, but in all other places the air was clear and very quiet, the temperatures were moderate, and the pressure relatively high. To the north of the Ohio Valley and Pennsylvania there was more or less rain, and in that district the weather would have been unfavorable for observing the eclipse.”

One Alabama Weather Bureau observer boasted that “never in astronomical history [had] a total eclipse of the sun been observed under more favorable conditions.”

What Meteorological Changes Did the Scientists Observe During the Eclipse?

Within 500 miles of the center of the totality, 62 Weather Bureau stations each took 25 sets of observations before, during, and after the eclipse. And, each set included barometric pressure, temperature, vapor pressure, cloudiness, and wind speed and direction. That’s over 9,000 observations just for this event!

Select Meteorological Observations at the Time of Totality

| Station | Station Pressure (inches of mercury) |

Temperature (°F) |

Wind (mph) |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Orleans, Louisiana | 29.966 | 76.0 | 3 SE |

| Mobile, Alabama | 30.005 | 72.8 | 3 NE |

| Montgomery, Alabama | 29.844 | 72.0 | 1 E |

| Charlotte, North Carolina | 29.285 | 67.0 | 8 SW |

| Raleigh, North Carolina | 29.712 | 71.1 | 4 SW |

| Norfolk, Virginia | 30.008 | 68.5 | 5 S |

From these observations, the scientists drew several conclusions:

-

The eclipse combined with the fair weather conditions did not produce a significant change in barometric pressure

-

The moon’s shadow caused a temperature drop of 3°F to 4°F

-

The eclipse caused wind speeds to decrease by about 1 mph but didn’t substantially or uniformly impact their direction

-

Vapor tension decreased by an average of 0.007 inches, leading to a slight increase in humidity

-

Cloudiness increased slightly during the hour before totality, with clearing in the hour after the eclipse

All of these observations and data helped the scientists learn more about how Earth’s atmosphere absorbs and radiates energy from the sun.

What Else Did the Scientists Learn on Their Eclipse Expedition?

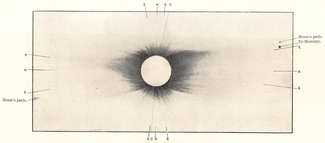

In addition to observing the meteorological impacts, the Weather Bureau scientists also studied the “shadow bands” produced by the eclipse. According to NASA, “shadow bands are thin wavy lines of alternating light and dark that can be seen moving and undulating in parallel on plain-coloured surfaces immediately before and after a total solar eclipse.”

The Weather Bureau sent out special instructions and forms for observing the shadow bands, and 34 volunteers provided accounts of what they saw as the bands passed over. Overall, they observed that the crescent-shaped bands were flickering, wavy, and unsteady. This made their speed difficult to determine. One observer even noted that the bands looked as if they were “struggling through two or more conflicting movements in the atmosphere itself.”

The Weather Bureau scientists eventually concluded that the shadow bands were largely a “meteorological phenomena” that might have been influenced by changes in humidity. But, scientists today still don’t fully understand what causes shadow bands to form.

Take Your Own Observations During the Great American Eclipse

On Monday, August 21, 2017, all of North America will be treated to an eclipse of the sun, which has been dubbed the “Great American Eclipse.” The path will stretch from Salem, Oregon, to Charleston, South Carolina. If you’ll be in the path of totality, you can take your own meteorological observations and see how they compare to those observed during the 1900 eclipse.

In fact, NASA is inviting eclipse viewers to participate in a nationwide science experiment by collecting cloud and air temperature observations and reporting them with their phones. And, all of the data you collect will be displayed on an interactive map.

To participate, download the GLOBE Observer app and register to become a citizen scientist. After you login, the app will explain how to make eclipse observations.

You can also download our keepsake form, grab your friends and family, and take your own eclipse weather observations like observers did during the 1900 event.

Safety First: Protect Your Eyes

Don’t forget! It’s important to take precautions when viewing the eclipse. Direct viewing of the partial phases can cause permanent damage to your eyes because of the intensity of the sunlight.The eclipse should only be viewed with protective eyewear designated for use during an eclipse. Ordinary sunglasses or 3D glasses lack sufficient protection. Also, avoid viewing through unfiltered cameras, telescopes, binoculars, or other optical devices.

However, if weather cooperates during the few minutes that the sun is completely eclipsed in totality, the brief interval is as safe to view as a full moon.