On June 28, 2013 near Yarnell, Arizona, a rogue lightning strike set in motion a series of events that would ultimately end in tragedy. Excessive heat, prolonged drought, and dry thunderstorms came together in a perfect storm to fuel a raging wildfire that burned 8,400 acres. By the time it was fully contained on July 10, the fire had damaged or destroyed nearly 130 buildings, injured over 20 people, and cut the lives of 19 Granite Mountain Hotshots woefully short.

Sparked by Lightning, Fueled by Drought

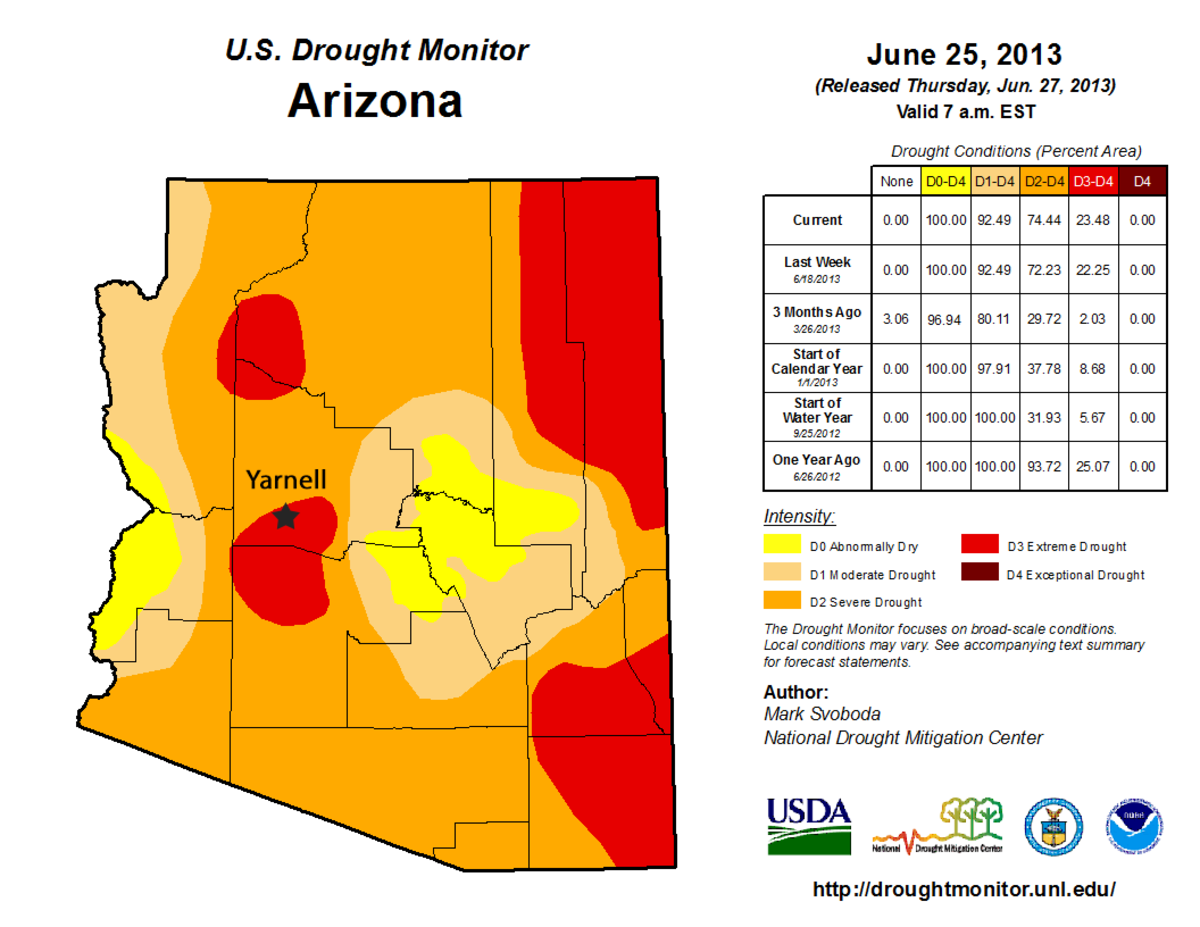

Before the start of the Yarnell Hill Fire, extreme drought—the second worst category according to the U.S. Drought Monitor—had been plaguing the area for months. And as is common in the Desert Southwest during summer, a monsoonal flow drew low pressure into the area, leading to the development of thunderstorms early in the morning of June 28. However, with the atmosphere so dry, the rain associated with the storms evaporated before ever touching the ground, leaving the lightning to ignite the drought-stricken vegetation that hadn’t burned in over 40 years, providing ample fuel for wildfires.

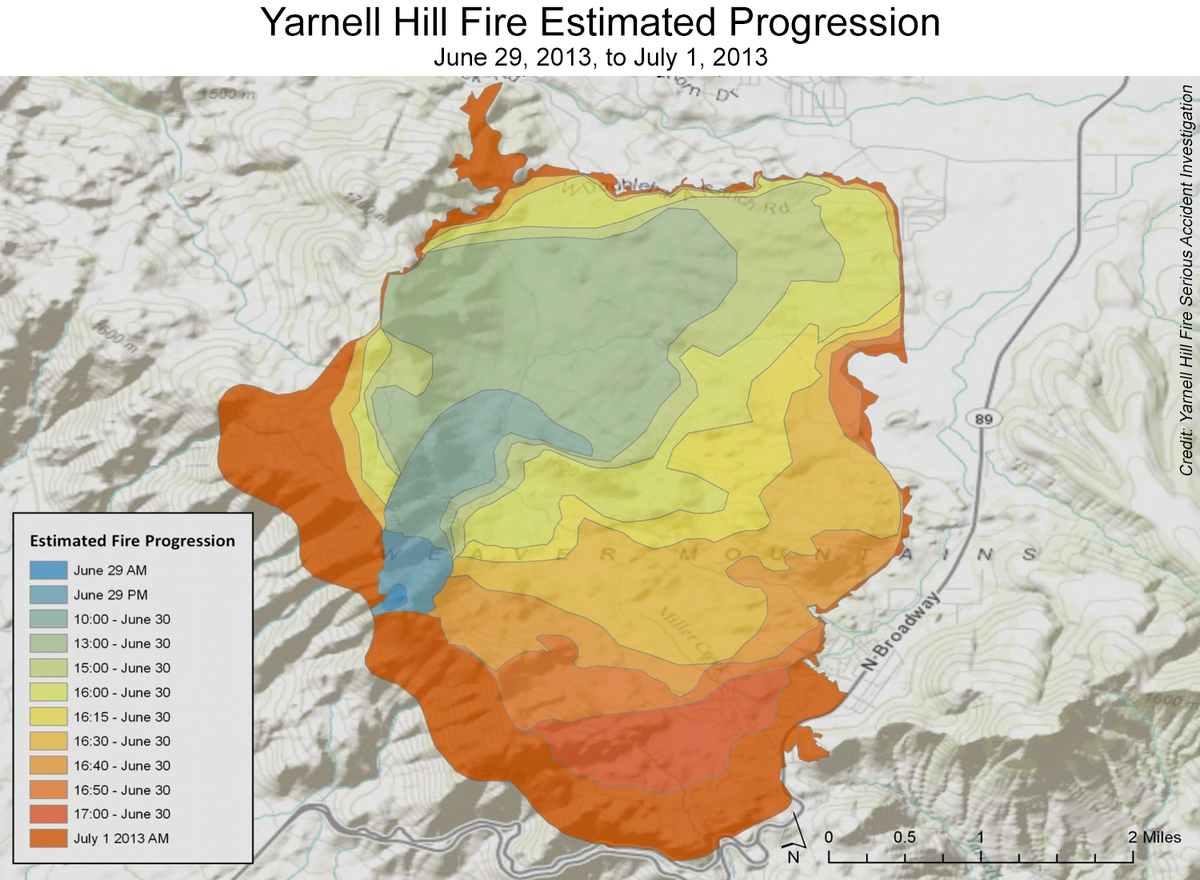

While lightning sparked the fire, strong winds and intense heat further fanned the flames. Two days after it began, the fire still remained small, having only burned about 500 acres. Everything changed on the afternoon of June 30 as temperatures soared.

At Prescott Love Field airport, about 30 miles to the northeast of Yarnell, an air temperature of 100°F was observed just before 1:00 p.m. Mountain Time. At that time, the relative humidity clocked in at just 10 percent with winds already gusting to 16 mph. Just before 2:30 p.m., wind gusts of nearly 22 mph and frequent lightning were noted as an afternoon thunderstorm entered the area. Within the next 90 minutes, the winds picked up dramatically with gusts reaching nearly 44 mph as the storm rolled to the southwest.

By 4:30 p.m., the storm’s outflow boundary—where the thunderstorm’s cooled air rushes out and away from the storm—had moved over the fire. This led to a dramatic change in wind direction and speed, sending the fire racing to the south three times faster than it had previously been moving. It was at that time that 19 members of the Granite Mountain Hotshot crew, working to contain the fire, became cut off from their escape route and ultimately perished.

The deadliest disaster for U.S. firefighters since September 11, 2001, the Yarnell Hill Fire and the tragic loss of the Granite Mountain Hotshots underscore the severe impact weather can have on people’s lives.

The Future of Wildfires

While we remember the past, we also use it to look to the future of U.S. wildfires. Since the early 1980s, the number of large forest fires in the western U. S. and Alaska has been increasing, according to the Climate Science Special Report. Scientists also expect the number of wildfires in those regions to continue to climb as the climate warms.

Wildfires similar to the Yarnell Hill Fire can develop at any time, making it extremely important to analyze them. NCEI’s historical wildfire data provide decision makers and constituents with the needed tools to ensure the public is better prepared for future fires. For more information on how you can prepare yourself, your family, and your friends for wildfires, visit the National Weather Service’s Wildfire Weather Safety website. Also, check the NOAA HRRR-Smoke Model for information about the path of smoke.