On March 27, 1964 (UTC) at 5:36 p.m. local time, the largest recorded earthquake in U.S. history struck Alaska’s Prince William Sound. The devastating 9.2 magnitude earthquake and subsequent tsunamis ravaged coastal communities and took over 139 lives.

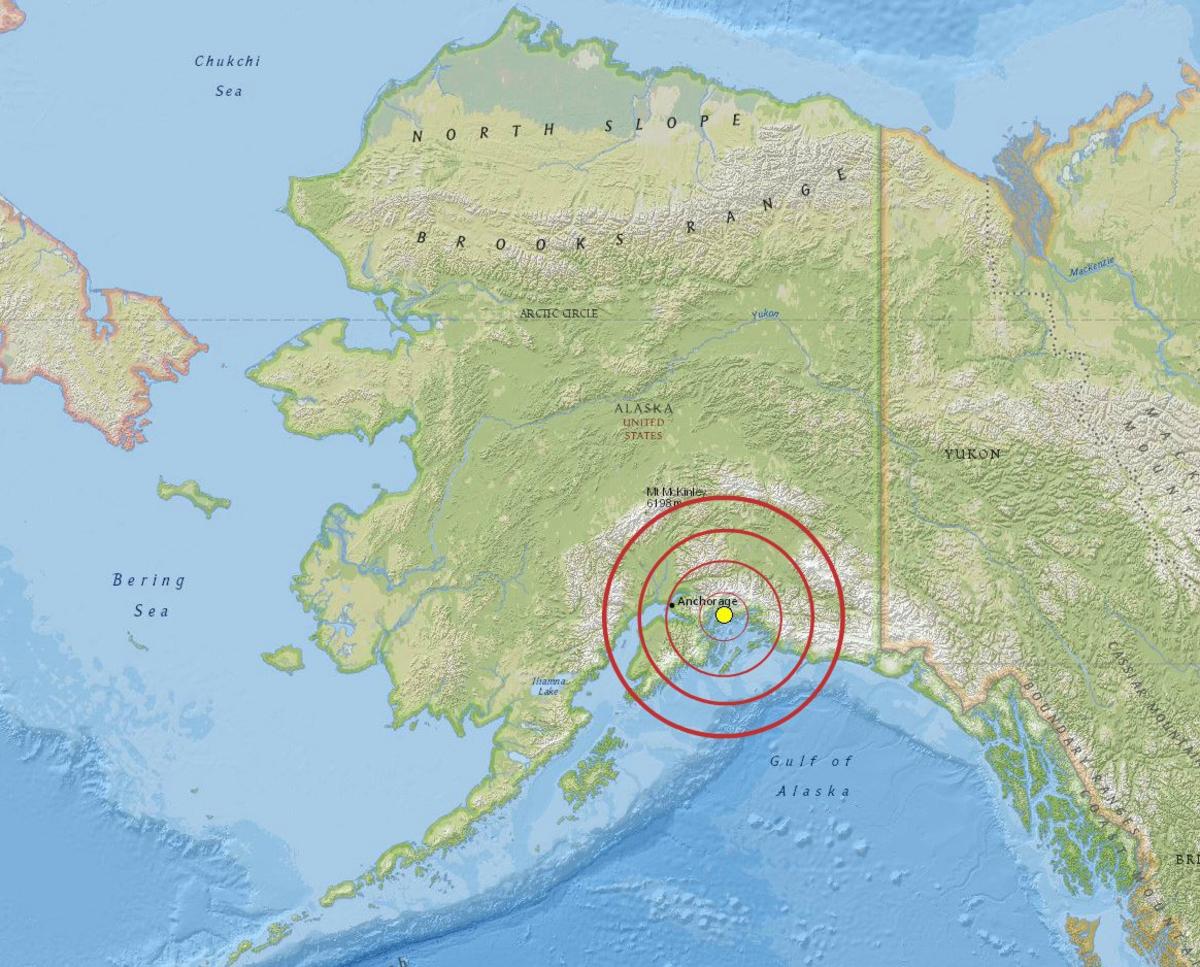

The powerful tremors lasted for nearly five minutes and were felt over a large area of Alaska and in parts of the western Yukon Territory and British Columbia. Aftershocks from the quake continued for three weeks.

The epicenter of the Great Alaska Earthquake was about 12 miles north of Prince William Sound and 75 miles east of Anchorage.

The epicenter of the Great Alaska Earthquake was about 12 miles north of Prince William Sound and 75 miles east of Anchorage.

Due to the long duration of the earthquake, catastrophic ground failures occurred. Ground failures are an effect of seismic activity in which the ground becomes very soft and acts like liquid, causing landslides, spreading, and settling. Massive landslides were triggered by the quake near downtown Anchorage and several residential areas, damaging or destroying about 30 blocks of dwellings and commercial buildings. Water mains and gas, sewer, telephone and electrical systems were all damaged or destroyed due to the landslides.

More Than Just A Quake

Earthquakes and tsunamis can happen along any coastline, at any time of the year, but Alaska is particularly prone to them because it sits on the convergence of two tectonic plates—the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate. At this boundary, the Pacific Plate slides beneath the North American Plate, causing the majority of Alaska’s earthquakes, including the 1964 earthquake.

Alaska’s continental shelf and North American plate rose over 9 meters during the earthquake. This sudden displacement of the ocean floor, along with earthquake-induced landslides, generated massive local tsunamis that resulted in 70 percent of the fatalities in southern Alaska. The tsunamis created by the earthquake reached land within a few minutes of the ground shaking and engulfed some areas as much as 170 feet above sea level. Scientists measured a wave runup of 220 feet in the Valdez Inlet.

Tsunamis caused loss of life, extensive flooding, and damaged harbors along the North American Pacific Northwest coast. Transoceanic tsunami waves swept across the Pacific and reached as far away as Hawaii and Japan. Seiches, a sloshing of water back and forth in a small body of water, were observed as far away as Louisiana, where a number of fishing boats sank in a harbor.

Though this hazardous event developed the moniker of the “Great Alaska Earthquake,” it was actually the ensuing tsunamis that did the greatest damage and took the most lives. Of the 139 deaths attributed to this event, 124 were directly caused by the tsunamis. Towns such as Whittier, Alaska, were inundated by tsunami waves before the earthquake had even subsided.

The Government Hill Elementary School in Anchorage was torn apart in a landslide created by the Great Alaska Earthquake.

The Government Hill Elementary School in Anchorage was torn apart in a landslide created by the Great Alaska Earthquake.

A Costly Disaster

The earthquake and ensuing tsunamis caused about $311 million in damages in 1964 (about $2.3 billion today).

President Lyndon Johnson declared the entire state of Alaska a major disaster area a day after the earthquake. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers spent about $110 million dollars repairing infrastructure, rebuilding communities, and clearing debris.

From Peril to Preparedness

Out of great catastrophe arises innovation and a new hope for the future of disaster preparedness. The aftermath of the Great Alaska Earthquake and Tsunami led to the creation of the NOAA National Tsunami Warning Center in Palmer, Alaska. Along with the NOAA Pacific Tsunami Warning Center located at Ford Island, Hawaii, the National Tsunami Warning Center monitors and warns for tsunami threats 24/7 throughout the year.

The invention of new tools and faster data processing have drastically improved NOAA’s ability to warn the public of tsunamis and to forecast their wave heights. Deployment of tools like deep ocean pressure sensors (Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis or DARTⓇ) are designed to ensure early detection of tsunamis and acquire data critical to real-time forecasts.

Today, almost 60 years since the Great Alaska Earthquake, the Tsunami Warning Centers issue tsunami warnings in minutes, not hours, after a major earthquake occurs. They also forecast how large any resulting tsunami will be as it crosses the ocean.

An effective tsunami warning system relies on the free and open exchange and long-term management of global data and science products to mitigate, model, and forecast tsunamis. NCEI is the global data and information service for tsunamis. Global historical tsunami data, including more information about the Great Alaska Earthquake, are available via interactive maps and a variety of web services.

For more information on how you can prepare for a tsunami, visit the National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program. For more earthquake and tsunami data, images, and educational materials, visit NCEI’s Natural Hazards website .