Barrier-breaking geologist and oceanographic cartographer

When educational lessons teach continental drift (that all of the continents were once connected), it is Alfred Wegener who is associated with the theory. Few hear of Marie Tharp, the pioneering mapmaker who discovered the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and proved the validity of the theory of continental drift.

Marie Tharp was born on July 30, 1920, in Ypsilanti, Michigan and grew up with a father who worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) as a soil surveyor. Despite early exposure to the science and mapmaking fields, Tharp chose to major in English and Music at Ohio University, graduating in 1943. She did not see a place for her in the STEM field as it was considered a “man’s place” at the time.

World War II was a catalyst for change when the workforce and universities started to recruit women to replace men joining the military to fight. The University of Michigan’s petroleum geology program recruited Tharp due to her undergraduate geology credit. She earned a master’s at Michigan then another one in Mathematics at the University of Tulsa. Tharp eventually found work at the Geological Observatory (present day Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory) at Columbia University.

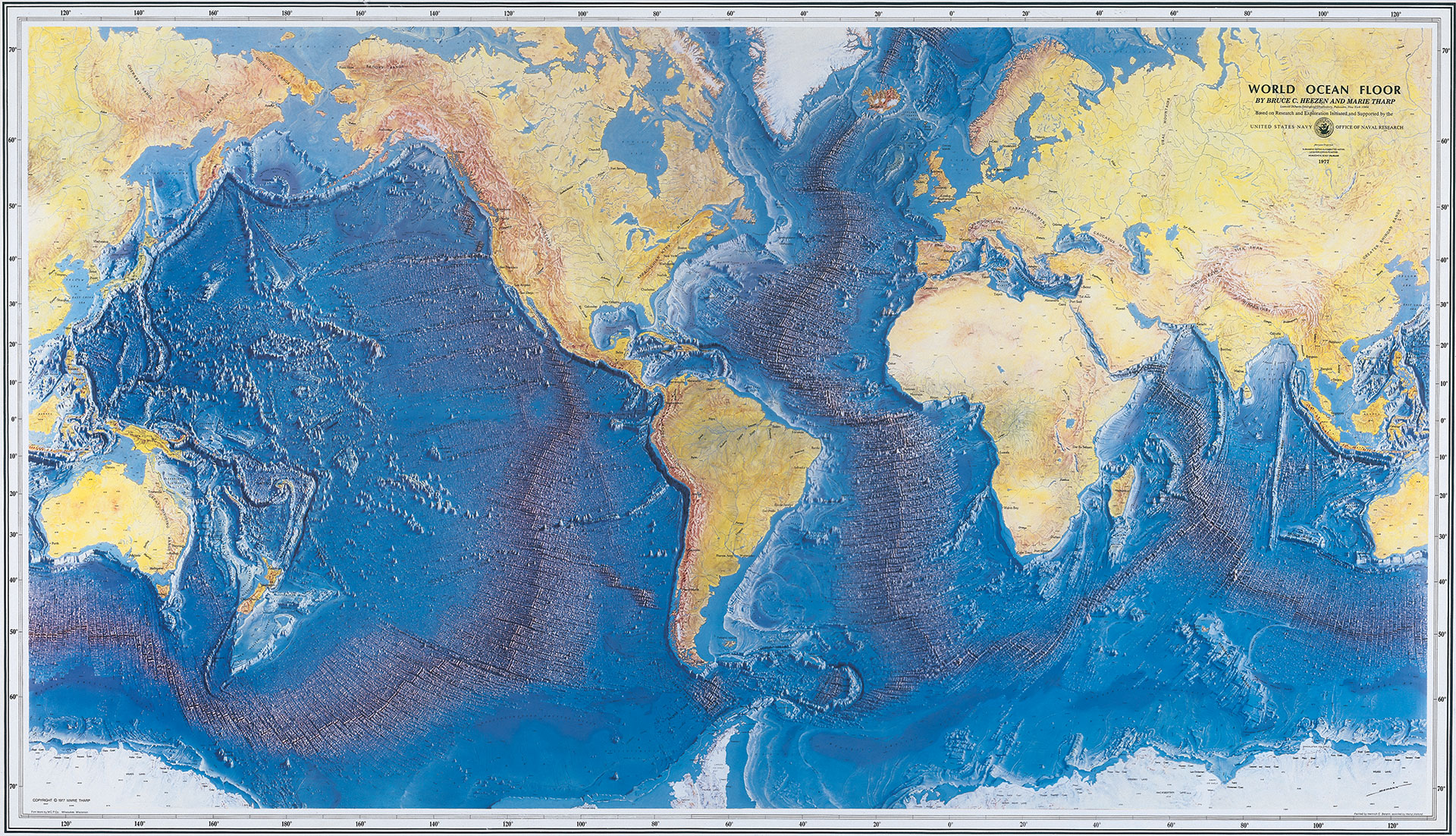

It was at this job she met Bruce Charles Heezen, an oceanographer and geologist. Since women were still not allowed on research vessels, Heezen would perform data collection at sea while Tharp remained in the office drawing maps from those data. When she received Heezen’s depth measurements, she plotted each point in physiographic diagrams. At this time the theory of continental drift had no scientific basis and little was known of the ocean’s floor, and the features of the ocean floor were being drawn out, many for the first time. It was through this work that she made the first systematic attempt to map the entire ocean floor. While looking at three transatlantic profiles, she compared the shape of the ridges she had drawn and immediately noticed a “V-shaped indentation in the center of the profiles or a rift valley, proving continental drift. Heezen dismissed what she discovered as “girl talk.”

Eventually, Heezen and the rest of the scientific community could not deny what Tharp found. Heezen and Tharp published the first physiographic map of the North Atlantic Ocean and then their research expanded to the rest of the ocean. After thirty years, the map of the entire seafloor was completed in 1977 based on the data from that era.

In addition to publications of her maps, Tharp went on to co-author many books and scientific papers. She not only validated continental drift, but made the ocean floor and related research more accessible. Marie Tharp died on August 23, 2006 at age 86. While she never worked for NOAA, the international community and NOAA routinely use products that leverage her work to this day, including the GEBCO grid, NCEI’s bathymetry data holdings and the NCEI-hosted GEBCO Gazetteer.